What Happens When the Automotive Industry Runs Out of Its Own Builders?

The skills gap isn’t a future problem. It’s a present collapse of identity, and no software platform or battery breakthrough will fix it.

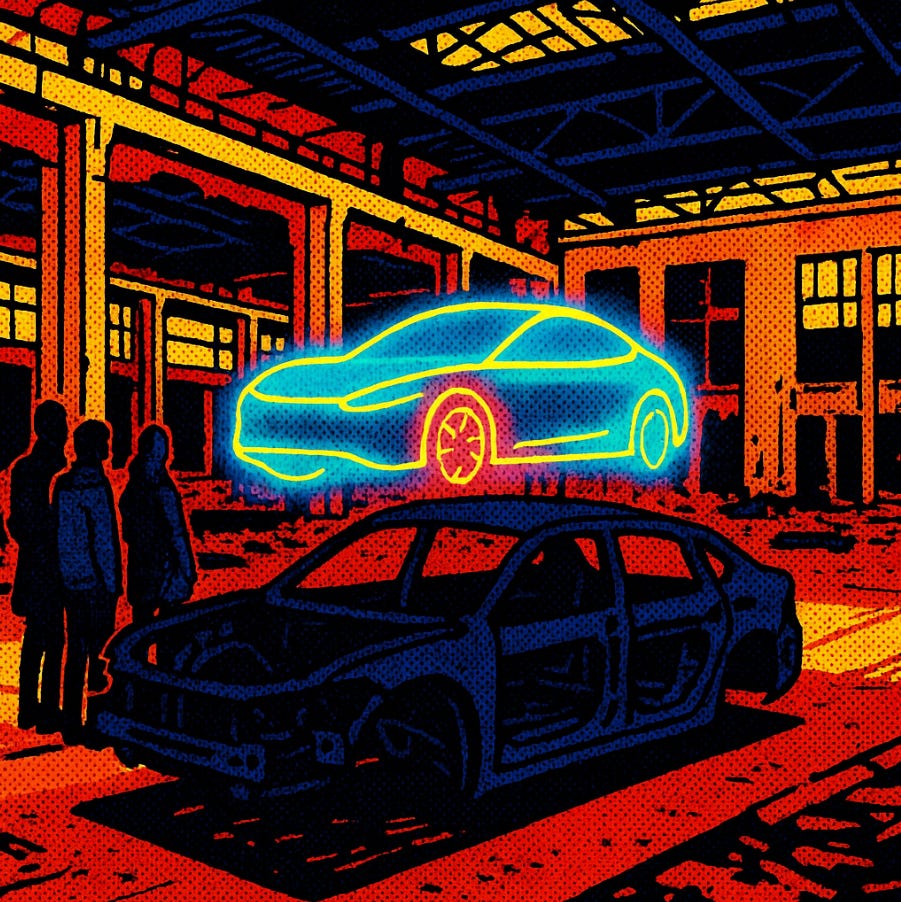

The future of the automobile is being sold as electric and software-defined, but the real story isn’t about batteries or code. It is about people. Behind every press release on EV range or digital platforms are workers, managers, and communities being torn apart by a transition moving faster than they can adapt. The vehicles may or may not succeed on the scale their champions predict, but the disruption is already here. The real question is whether the industry will have anyone left to carry it forward.

For a century, the defining strength of automotive was its people. Engineers who could hear a misaligned gear and know the fix without a manual. Technicians who could rebuild an engine from memory. Managers who knew how to choreograph supply chains that stretched across continents. That knowledge was an inheritance, passed down through apprenticeships, practice, and scars. Today it is being devalued at speed. OEMs and Tier-1s want software developers, cybersecurity specialists, and battery engineers. McKinsey projects a shortage of 1.1 million software engineers in automotive by 2030. LinkedIn found only 2 percent of automotive engineers with meaningful software skills. Battery experts are so scarce that companies raid one another like it is open season. And combustion engineers with twenty years of mastery suddenly find themselves losing jobs to graduates half their age who can code Python but have never survived a validation cycle. What is being lost is not only capability, but identity.

Reskilling is the corporate mantra, but the math does not work. Volkswagen promised to retrain 10,000 workers for EV production. Two years in, fewer than a third had made the transition. Ford has spent billions on retraining since 2020, yet the disruption still outpaces the learning. A machinist can complete a course in automation, but that does not make them fluent in data pipelines. A manager who spent a career negotiating transmission contracts is not suddenly a cloud deployment strategist. Some find ways to bridge old and new. Most do not. The gap is technical and cultural.

Tier-1 suppliers are caught in the most brutal version of this shift. Their legacies were built on precision machining, stamping, injection molding, the quiet mastery of parts that never failed. These divisions still generate profit, yet the prestige has shifted to loss-making digital units that exist more on slides than in revenue. Meanwhile, Tier-2 and Tier-3 suppliers are skipping past them, selling innovations directly to OEMs. Departments built to integrate smaller suppliers now watch themselves become redundant. The machinists feel abandoned. The digital hires wonder whether they have joined a forward-looking company or an aging one trying to fake it. Nobody is sure which identity will win, or if either will.

The polite phrase for the consequences is supplier rationalization. On the ground, it looks like layoffs, closed plants, and gutted towns. Stellantis shut its Michigan V6 engine plant in 2024, cutting 1,200 jobs. Belvidere, Illinois, saw its tax base collapse after closures. Schools suffer, main streets hollow out, and entire communities lose the only identity they ever knew. New investments arrive, like CATL’s $7 billion battery facility in North Carolina, promising 3,000 jobs. But the skills required are not the ones displaced workers possess. To them, corporate “progress” looks like betrayal disguised as opportunity.

If workers feel abandoned and executives talk in abstractions, the heaviest burden is in the middle. Middle managers are told to defend profitable combustion programs while leading underfunded digital initiatives, often with teams they cannot support and tools they barely understand. A 2025 Automotive News survey found that 60 percent were already burned out, with many leaving for other industries. They were once the interpreters between boardroom theory and shop floor reality. Now they are being hollowed out, asked to deliver miracles without a mandate. When the middle collapses, execution collapses with it.

Workers are not blind to the pattern. The United Auto Workers strike in 2023 secured wage hikes and EV-specific protections, but it was also a warning. They know EVs require fewer parts, with BCG estimating 30 percent fewer than combustion vehicles. They know automation will take more. They have heard retraining promises before—during outsourcing, during offshoring—and they remember how those promises ended. In a 2024 UAW survey, only 15 percent of retrained workers believed their new skills would secure stable jobs. Their skepticism is not fear. It is history.

Global competition only accelerates the fracture. Chinese automaker BYD, with its vertically integrated supply chain, delivers EVs 20 percent cheaper than Western rivals. European automakers drown in labor law disputes and fights over insourcing. In the U.S., reshoring is largely automation in disguise. GM’s Ohio battery plant, set to open in 2026, will employ 1,300 workers—half of what a comparable combustion facility required—because robots will do the rest. One kind of knowledge is being swapped for another, and the exchange is not remotely fair.

The industry sells this transformation as a technological triumph. EV range. AI-driven features. Factories humming with automation. But the real test is not whether the technology works. It is whether the people who built this industry have a place in its future. The companies that survive will not be the ones with the slickest dashboards or the most aggressive software roadmaps. They will be the ones that invest in apprenticeships measured in years, not months. They will be the ones that forge public-private partnerships like Michigan’s $100 million EV training fund. They will be the ones that align new opportunities with the workers being displaced instead of pretending courseware can close the gap.

If the industry cannot solve for its own people, then no battery breakthrough, no digital platform, and no glossy investor deck will save it. The history books will not ask how advanced the vehicles were. They will ask what this industry did to the people who built them. And if the answer is abandonment, then the real revolution will not be electric or software-defined. It will be the slow death of belief that this industry is still worth giving a life to.

#automotive #ev #sdv #workforce #skillscrisis #labordisruption #futureofwork #manufacturing #humanfactor #industrytransformation

Michael Entner-Gómez is a strategist, technologist, and writer focused on the convergence of the world's most critical infrastructure sectors: energy, transportation, and telecommunications. Using a systems-thinking approach, he helps industry incumbents and disruptors future-proof their operations, scale complex platforms, and navigate the shift to software-defined everything.

This article is not sponsored, not paid, and not written to please. It’s written to inform.